There are rare instances in the realm of motorcycle design where an icon emerges. These are machines so radical that they serve as a clean break from the standards of the past, thereby setting a new template and pushing the high-water mark up the wall a few extra feet. To truly be an icon, they must influence subsequent processes and inspire a new thread in motorcycle design; one-off machines that immediately fade into obscurity won’t do. They can be new standards of beauty, of performance, of chassis design, or of templates for hitherto untried categories (or some combination of all four). These motorcycles are often the product of years of research and countless design hours—produced by multi-billion dollar corporations that can afford to take a risk once and a rare while.They are not often produced by a tiny boutique manufacturer that has built less than a thousand machines, conceptualized by men who were not classically trained “designers” with decades of experience under their belts.

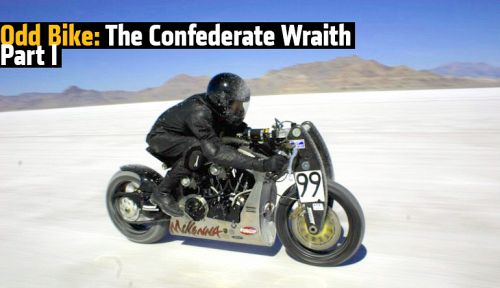

The Confederate Wraith was one such icon that emerged from Southern Louisiana like a thundering slap in the face to all that the motorcycle industry held dear. It was an absolute break with tradition, a bold insult to the long-held standards of a conservative industry, and a new way of conceiving of the motorcycle that was unlike anything that had preceded it. It was a product of looking forward while respecting history, a curious mixture of old and new ideas blended into a stunning machine that was as brutal as it was intelligent.

The story of the Wraith must begin, inevitably, with the story of Confederate. Founded in 1991 by H. Matthew Chambers, Confederate was as much a product of Chambers’ ideology and uncompromising principles as it was the result of a desire to introduce a new concept in American motorcycle manufacturing. A long time motorcyclist and passionate student of Southern history, Chambers was far from the prototypical entrepreneur. After a series of career changes he earned a law degree and practiced as a trial lawyer in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He established a successful practice and earned a tidy income, but dreamed of contributing something greater to the world.

After winning a particularly grievous personal injury case in 1990 and earning a considerable fee, he sold his share of the practice to his partner and with a million dollars of his own money set out to start his dream project: An American motorcycle that would eschew the stagnant design and commercialization of the American market in favour of an heirloom-quality machine that would have dominating performance. His plan would spark the renewal of an industry that had not existed in the Southern United States since Simplex had faded into history. In conception and execution, it would prove to be a labour of love born of high-minded ideals and a desire to renew craftsmanship in an industry that had become driven by profit margin.

Chambers’ ideas were as esoteric as they were inspiring—a lone voice in the wilderness calling for a conceptual shift in the way motorcycles were designed and built in America. Design and construction would be unhindered by considerations of profits. Individualism would be emphasized, as would mechanical detail and craftsmanship. Nothing ancillary or unnecessary would be present. The machines would be raw and would command respect from their riders, channeling their uncompromised nature through their performance. Chambers’ tenets called for a renewal of what he called “The American Way” and the abandonment of “The American System”: at its core the idea is to bring back quality, pride and craftsmanship in American manufacturing instead of promoting materialism, stagnant design, and marketing falsehoods. This rhetoric continues to inspire confusion among the masses who have been weaned on cheap mass-produced motorcycles fluffed up with contrived links to a mythos cooked up in the boardrooms of multi-billion dollar corporations.

24

Comment