Question: On several occasions, you’ve mentioned the handicap Ducati has with regard to weight bias and engine placement. The engine is heavy in back, where the crank and transmission are. So why not turn the engine around? Crankshaft toward the front, one cylinder pointing up, the other back. Admittedly, not trivial to do, but Ducati has plenty of resources.

Answer: In the early 1990s, a major motorcycle-handling problem was “squat and push.” During off-corner acceleration, if the back of the machine squatted down from acceleration weight transfer, the front end would become too light to steer and the bike would “push” (fail to hold the line and run wide).

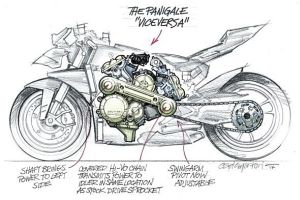

Öhlins studied this and wrote a math analysis that was circulated to teams. It showed how to use two other chassis forces to oppose squat: (1) the rear wheel tries to “run under” the bike, tending to extend the rear suspension; and (2) chain tension because it does not act parallel to the central plane of the swingarm, generates a tangent force, also tending to extend the swingarm.

With this knowledge, teams quickly made swingarm pivot locations adjustable so they could vary the anti-squat force. Ducati, however, continued to pivot its swingarm on a lug integral with the gearbox, making pivot position adjustment impossible. Ducati’s stiff rear spring overcomes the squat force, but it causes a more rapid loss of tire properties. This problem plagued Ducati’s Superbike racing effort for years.

If, as you suggest, the gearbox were placed ahead of the engine crankshaft for a more advantageous forward weight distribution, some system of chain idlers would have to be implemented to restore the necessary sprocket/pivot relationship. Very possibly this could be achieved. The tendency in racing, however, is to make small, incremental changes that are easily reversed if they fail to meet their objective.

Ducati, for marketing reasons, feels it must use the “signature” 90-degree cylinder angle, despite its packaging bulk. Sometimes, companies must make choices. When Yamaha hired Valentino Rossi, Masao Furusawa gave him four prototype bikes to test—two with 90-degree cranks and two with 180-degree cranks, with one of each pair having Yamaha’s signature five-valve Genesis cylinder head and the other a conventional four-valve head. Rossi went quickest with (and liked) the four-valve engine with a 90-degree crank. The result? MotoGP titles for Rossi and Yamaha in 2004, 2005, 2008, and 20

24

Comment